Newsletter #2 October 2025

CRR

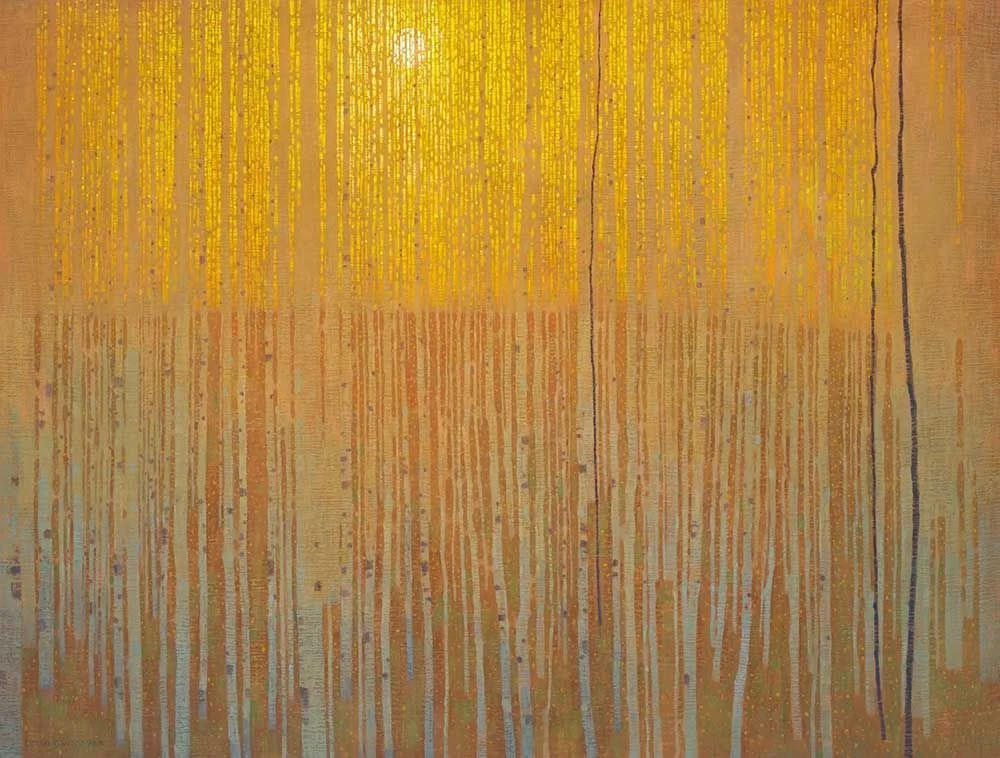

David Grossman, Bright Autumn Patterns, oil on linen panel

October, and as I was walking along the sidewalks that are littered with hundreds of yellow leaves this time of year, I felt, for a brief moment, the words of the peripatetic poet Bashō amidst all the falling, “To live poetry is better than to write it.”

When I first began reading the poetry of the Edo period of Japan, I did not yet know how to talk about the poems. I was very young. I imagined people who wrote great poetry had figured out what to do in rooms, and I could not describe why I felt drawn to the word ocean, but I could confirm, undoubtedly, that I was devoted to the possibility that a poem could allow a person to become one in taste with its waters.

Entering the beautiful multiverse of image and reflection that is Japanese poetry at the tender age of nineteen felt as affecting as it did daunting—yet the simplicity so significant in contrasting my assumptions of depth. There is the famous Jane Fonda quote, “I was so old at 20.” I, too, felt attitudinally old, caught up in my own rigidity and dissatisfaction. And as you might imagine, this was neither spiritually nor literally efficacious, because if I had been asked to play around with Bashō’s words, I would have likely come up with something like this: “It is better to write poetry than to live.”

How backward! I remember one week I carried a packet of Kobayashi Issa’s poems in my backpack, with a highlighter the color of a tennis ball smeared through the lines: “White saxifrage flowers / all around my bedroom bring / me lasting light.” I loved how, in that poem, Issa focuses on the marvel of a seemingly mundane space, and, at the same time, produces a continuation effect with the word “lasting” so that the poem is not merely restricted to ending on the page, but rather sustained by the imagery of natural recurrence.

It took me years of regression to appreciate the opacity of poets like Bashō and Issa, specifically their integration of humor, imperfection, and the temporality of nature. “Go to the pine if you want to learn about the pine; go to the bamboo if you want to learn about the bamboo,” says Bashō to his students as they ask him about life.

Here is a summary from some of those teachings:

Detach the mind from self

Enter into the object

A poem forms itself

Upon reading those words, I feel, most importantly, an invitation to decenter in order to invoke creative thought. How special, that these voices, centuries old, seem so pertinent to our relationship with ourselves?

When we first began the idea of creating Cherry Road, I couldn’t help but think back to my time discovering those precious and ancient words. It’s been fundamental to trace the history of the image and the power of language to encourage our decentering, and to find connection in that decenter through the writing.

At the most basic level, shouldn’t we feel excited by the preciousness of what we still have to learn? It’s sort of disguised, like when I notice people become shy and soft when they realize they haven’t read as much as they ought to. Instead, I think it is fruitful, to have come all this way and still have more to read.

Which is to say, this first issue of Cherry Road Review began thinking of this: what happens when we give the object its say—when we “go to the pine,” then stay long enough to speak back? Our hope was (and is) to practice an honest departure but also a certain reserve, to understand circumstance.

I must also add that I am grateful to everyone who has submitted thus far to the issue. We have received more than 1,000 individual submissions to consider, and are still working on sorting through your work. If you have submitted, please expect a response this month—and thank you again for your patience.

Currently, the fall issue is scheduled to release in early November. We are so excited to share this collection with you all. In the meantime, you can join the conversation via our Instagram (@cherryroadreview) and Bluesky (cherryroadreview.bsky.social). We’d love to hear from you.

Charlotte Ungar

Editor, Cherry Road Review